Going Clear, by Lawrence Wright, is a book that was characterized, to me, by its use of pathos and logos. The narrative of the religion Scientology is laid out very clearly, and each step of the way is backed up by primary source documents or accounts. Like any good non-fiction writer, Wright did his research. However, interspersed between the purely factual accounts of events, Wright inserts his personal opinions, which is his right as an author. And although his opinion may agree with the majority (that Scientology is a strange and scammy "religion"), it's his opinion nevertheless. But I think that's the sort of thing one should expect from any sort of book. Nothing is free of bias. I actually enjoyed reading some of his judgments and thinking to myself, "Well, that's not completely true." This book was good at challenging my beliefs and providing me with the evidence to create my own viewpoints while also showing how they could support another.

I think that the author's purpose in writing this book was to delve deeper than most people are willing into the subject of Scientology, and to provide a comprehensive look at its progress, from its beginning to the present. It's a known fact that the Church tends to prosecute those who speak badly about their religion, so Wright took a risk in writing this book. I'm sure he felt it was necessary, though, to exercise his freedom of speech and provide information (biased, sometimes, but sometimes very objective) about an artifact of American culture. His use of quotes, statistics, and documents helped give the reader a good overall view of Scientology's development. It's effectively impossible to have a non-fiction informational book that is not well-researched, and I believe this book was extremely well-researched. However, it also contained perspectives and viewpoints from the author himself and in quotes from people directly involved with the religion that provided some pathos, by making the reader consider their own opinions and feelings regarding the subject.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

TOW #7 - "Pets Allowed" (Written)

Pets Allowed, by Patricia Marx, is a comedic tale of her adventures in New York City on five different days with five different "emotional support" animals: a snake, a pig, a turkey, an alpaca, and a turtle. Her purpose is to convince pet owners that the concept of an emotional support animal is ridiculous. Emotional support animals (ESAs) are different from service dogs, who are able to perform specific tasks that aid their owner. ESAs are simply there to comfort their owner, and since that is such a broad definition, Marx proves that you can quickly and easily (for about $100-$200) register any animal, no matter how ridiculous as an ESA.

People obviously take advantage of this. The law does not require any businesses to allow ESAs inside, although it is required that they allow service dogs in. However, there is a gray area in terms of the general public's knowledge of these laws, so Marx was able to take her menagerie into restaurants and stores by showing them a letter from a random therapist she found online that approved her animals for emotional support. She managed to get an alpaca into a historical house (which should never be allowed, for obvious reasons) simply by flashing the letter from her sketchy shrink. Her argument is accentuated by its ridiculousness -- she uses hyperbole by representing the worst-case situation to show how people breaking the law in normal life have potential to cause disturbance and annoyance to others, simply for their own comfort.

Her article was not completely for argumentative purposes, however. If it had, she could have just taken one ridiculous animal out. However, to amass as many humorous anecdotes as possible, she took five animals, each of which created their own unique situations. The article comes with pictures of her pushing the pig around in a stroller, or carrying him into the cabin on the plane (she brought her pig on a plane!) to show the pilot, and pictures of her turkey on a bus and her snake wrapped around her neck. She aims to amuse and use that amusement she creates in the reader to further her argument.

People obviously take advantage of this. The law does not require any businesses to allow ESAs inside, although it is required that they allow service dogs in. However, there is a gray area in terms of the general public's knowledge of these laws, so Marx was able to take her menagerie into restaurants and stores by showing them a letter from a random therapist she found online that approved her animals for emotional support. She managed to get an alpaca into a historical house (which should never be allowed, for obvious reasons) simply by flashing the letter from her sketchy shrink. Her argument is accentuated by its ridiculousness -- she uses hyperbole by representing the worst-case situation to show how people breaking the law in normal life have potential to cause disturbance and annoyance to others, simply for their own comfort.

Her article was not completely for argumentative purposes, however. If it had, she could have just taken one ridiculous animal out. However, to amass as many humorous anecdotes as possible, she took five animals, each of which created their own unique situations. The article comes with pictures of her pushing the pig around in a stroller, or carrying him into the cabin on the plane (she brought her pig on a plane!) to show the pilot, and pictures of her turkey on a bus and her snake wrapped around her neck. She aims to amuse and use that amusement she creates in the reader to further her argument.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

TOW #6 - "Don't Eat Before Reading This" (Written)

This piece by Anthony Bourdain, who worked his way up to owning his own restaurant from being a dishwasher, reveals the secrets behind a usual New York professional kitchen that most people don't know about. His diction is very frank - he does not hold back from telling the reader about the disgusting and disease-ridden conditions going on behind their favorite restaurants. He uses words like "cruelty and decay" to really get across his message that kitchens are not fairy tale lands.

He uses juxtaposition of the quaint French terms that people think chefs use with the coarse Spanish that they actually use. This helps emphasize the difference between perception and reality. However, he assures the reader that while there can be violent spats, no one actually uses their readily available weapons (knives and meat mallets) for evil. So there is a soft side to the kitchen life, but it doesn't come out very often.

He references the Department of Health a few times, mostly to tell the reader that many of their regulations are ignored. This may be the reason for his humorous title, which tells the reader that what they're about to read will not sit well with them or their dinner. It also establishes a light-hearted tone in what might otherwise be a serious exposé. He doesn't believe that anything that goes on in these kitchens is truly bad, just unfortunate truths of the industry.

Bourdan introduces terms to the reader and defines them right away, which helps give them a quick insider's look. Just learning the terminology of a certain profession gives a really good glimpse into how it works and what the most important aspects of it are -- since the things that are used most often will probably get unusual names. And if a name is disparaging (like "coffee filters" for the tall paper chef hats most people imagine), it clues you in that that object is less important, or annoying, or silly.

He uses juxtaposition of the quaint French terms that people think chefs use with the coarse Spanish that they actually use. This helps emphasize the difference between perception and reality. However, he assures the reader that while there can be violent spats, no one actually uses their readily available weapons (knives and meat mallets) for evil. So there is a soft side to the kitchen life, but it doesn't come out very often.

He references the Department of Health a few times, mostly to tell the reader that many of their regulations are ignored. This may be the reason for his humorous title, which tells the reader that what they're about to read will not sit well with them or their dinner. It also establishes a light-hearted tone in what might otherwise be a serious exposé. He doesn't believe that anything that goes on in these kitchens is truly bad, just unfortunate truths of the industry.

Bourdan introduces terms to the reader and defines them right away, which helps give them a quick insider's look. Just learning the terminology of a certain profession gives a really good glimpse into how it works and what the most important aspects of it are -- since the things that are used most often will probably get unusual names. And if a name is disparaging (like "coffee filters" for the tall paper chef hats most people imagine), it clues you in that that object is less important, or annoying, or silly.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

TOW #5 - "Before the Internet" (Visual)

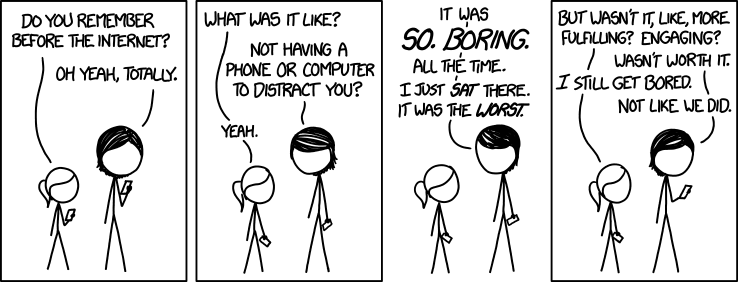

This is a webcomic written/drawn by Randall Munroe, who has been making comics like these since 2005, and it features a little girl holding a phone, talking to an adult also holding a phone. It pokes fun at how everyone laments the loss of a "fulfilling" and "real" life after the advent of the internet. The young girl, having heard this her whole life, assumes it must have been better back then, but is quickly shot down by the adult, who assures her that it was terrible.

Readers of this comic, the majority of whom are in their twenties to thirties (though there are younger readers), lived most of their childhood without a constant stream of internet in their hands. They themselves are probably guilty of trumpeting how they miss the "good old days" - but halfway through the comic, when the expected response from the adult is "oh, life was better, we went outside, we were more creative, etc." -- she gives a frank, honest reply. One can almost hear the tone of voice she uses, which the author conveys with the large, bold, italic text in the middle of the comic.

The stick figure characters are drawn in black and white, with no facial expressions. All the emotions have to be conveyed with stance and word choice, which this author does very effectively. The adult looks at the child very seriously when telling her how boring it was, then turns nonchalantly back to her phone when brushing off the kid's clarifications. "Wasn't worth it." It's obviously said in an off-hand, "of-course-not" manner, which the reader infers simply from the position of the stick figure's head and the short sentence.

Something that this author is famous for is putting mouseover text on all his comics, meaning that if you hover over the picture for a few seconds, a box will pop up with a continuation of the joke. The text on this one is "We watched DAYTIME TV. Do you realize how soul-crushing it was? I'd rather eat an iPad than go back to watching daytime TV." It's a silly joke for readers who are "in on the secret" to discover. It also adds a little more to the "argument" of the comic.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)