This article by Maria Konnikova begins with a question that many people want to hear the answer to. Figuring out how to function with less sleep is an obsession that is fueled by energy drinks, coffee, and loud alarm clocks. Although her title isn't in the body of her essay, it's an excellent hook that leads the reader into what she's about to discuss and promises the information that will come later in the essay.

She begins with a generous amount of logos, spouting statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention left and right. She hits the reader with the fact that 15.5 million people fall asleep while driving each month, which makes a compelling argument for finding a way to function with less sleep, especially since 35% of Americans get less than seven hours of sleep per night. The recommended amount is eight. That's a scary discrepancy.

She slowly introduces Dr. Pack, and his journey towards finding the gene mentioned in her title. She uses a narrative mode of writing to describe how he began in pulmonary studies, but felt compelled to help others with his work, and pulmonary studies weren't making an impact. So he did some research on sleep apnea, and that's how he transitioned into sleep studies. Konnikova assumes that her audience is interested both in the "sensationalist" discovery that drew them in, as well as the backstory behind it, so she explains some of the study and how he discovered and tested the gene that allows people to sleep less.

However, there is a saying that if a news article asks a question, the answer is almost always "no". Disappointingly, Konnikova closes her piece with "the best answer may still be the one we don't particularly want to hear: get more sleep -- as often as we possibly can." Though she wrote an interesting article describing a new scientific discovery, her title was a little over-sensationalist. This gene is not something that can be inserted into everyone. Though she wrote a good, interesting article, her title is slightly misleading, which might reduce her ethos in some readers' eyes.

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Sunday, December 14, 2014

TOW #13 - "The Language Instinct" (IRB)

My favorite question to ask bilingual people is "What language do you think in?" From the beginning, though, this book showed me pretty quickly how ridiculous of a question that is. Though I got a little lost in the technical details of noun phrases and how they're laid out and what goes where, I now understand that everyone just thinks in "mentalese" -- a language with representations of concepts without specific words attached to them. I thought an especially interesting analogy that Stephen Pinker introduced was the idea that young children have all these switches in their brain when they're first born. These switches are just waiting to hear the language that the child is surrounded with to begin flipping up and down to create the mental grammar that the child will then plug the vocabulary that they learn into. I thought that was so interesting, because of how natural "blue ball" feels to me, and how strange "ball blue" is. I just had the "adjectives go in front" switch flipped when I was young.

The explanations I've read so far in this book have me wondering whether there is a way to mess with the switches in people's heads to make learning second languages as an adult easier. And I also wonder whether anyone is truly natively fluent in two languages, even if they learned both while they were babies. One of the languages had to flip the switch first, right? Can a person have two mental grammars? My friend Sun, who was raised speaking Korean until fourth grade and then learned English, is very good at both languages, but she tells me that Korean-Americans who grew up learning both at the same time aren't very good at either. I don't know if this is inaccurate anecdotal evidence, but it makes sense with Pinker's mental grammar theory. Young children trying to sort out which rules go with which languages will understandably make a few mistakes, and therefore have some rules inextricably linked with the wrong language from very early on. But learning one set of grammar very well, and then later on deliberately introducing a second seems like it would disturb the first language less.

Something that Pinker does that I like is use diagrams to help illustrate his point. All the grammar jargon can get mixed up and lost in the reader's head, but having pictures to sort it all out can help. The reader can clarify, confirm, or correct what they read with what they see. It's also helpful to universalize what he's talking about. In his writing, he often uses English as an example because it's the language that the reader is assumed to be most familiar with, and it's the language he is most familiar with. However, most of the rules he talks about apply to all languages, so the diagrams give a helpful picture of the overall system and how it works with all languages.

The explanations I've read so far in this book have me wondering whether there is a way to mess with the switches in people's heads to make learning second languages as an adult easier. And I also wonder whether anyone is truly natively fluent in two languages, even if they learned both while they were babies. One of the languages had to flip the switch first, right? Can a person have two mental grammars? My friend Sun, who was raised speaking Korean until fourth grade and then learned English, is very good at both languages, but she tells me that Korean-Americans who grew up learning both at the same time aren't very good at either. I don't know if this is inaccurate anecdotal evidence, but it makes sense with Pinker's mental grammar theory. Young children trying to sort out which rules go with which languages will understandably make a few mistakes, and therefore have some rules inextricably linked with the wrong language from very early on. But learning one set of grammar very well, and then later on deliberately introducing a second seems like it would disturb the first language less.

Something that Pinker does that I like is use diagrams to help illustrate his point. All the grammar jargon can get mixed up and lost in the reader's head, but having pictures to sort it all out can help. The reader can clarify, confirm, or correct what they read with what they see. It's also helpful to universalize what he's talking about. In his writing, he often uses English as an example because it's the language that the reader is assumed to be most familiar with, and it's the language he is most familiar with. However, most of the rules he talks about apply to all languages, so the diagrams give a helpful picture of the overall system and how it works with all languages.

Sunday, December 7, 2014

TOW #12 - "Girl Humor" (Visual)

This comic, by Kate Beaton, points out the misogynistic way that humor is considered in the "male domain". Many people just assume that only men can be funny, that female comedians are terrible, that they need to qualify funny women as out of the ordinary. At the same time, she criticizes the way female comedians feel compelled to make jokes solely revolving around their gender, whereas male comedians have a much wider variety of topics. She uses a sardonic tone and parodies "typical" female humor in order to point out how ridiculous the notion that girls can't be funny is.

For some background, Kate Beaton runs a website called Hark! A Vagrant, where she posts comics that often play off of historical or literary themes. It's sophisticated humor that deserves respect, so naturally, random men online harass her about her totally irrelevant gender. She aims to humiliate them with this comic, and show them how ridiculous their "compliment" seems. Her entire website serves as support to her argument, showing that women are capable of sophisticated humor. A lot of the famous female comedians joke about the sorts of things Beaton discusses in the fourth panel because they are expected to, and because if they broke out of that shell, they would receive comments like the ones in the second panel. However, repeating the same jokes about the same tired topics gets boring after a while, which is probably where the "women aren't funny" idea came from, and is perpetuated by close-minded people.

Her last panel also shows the simplicity of the typical female humor, leaning back and acting as though the fourth panel which probably took seconds to make was enough to create humor. However, her real comics actually take time and effort to produce, and she tries to get that across to man who emailed her. People -- male or female -- who put time and effort in the things they create can be equally as funny. Those who simply make easy jokes that are expected of them will not be as funny. Beaton works hard on her humor, and deserves respect worthy of a person, not just a woman.

Sunday, November 16, 2014

TOW #10 - "Insert Flap 'A' and Throw Away" (Written)

This essay by S.J. Perelman is a humorous piece angrily criticizing the impossibility of the directions included with DIY project. The author is a father of two children, which implicitly conveys to the reader his familiarity with construction projects such as these, since he's the member of the family who, at least in the social culture of the 1940's, is expected to take charge. He uses irony and hyperbole to create a picture of insanity that connects to the feeling that most readers are familiar with when dealing with DIY projects. The main narrative of the essay deals with him putting together a toy truck for his children on Christmas, which should be an easy task, but is absolutely not.

His irony manifests itself in humorous one-liners. He says that the kit "was simplicity itself, easily intelligible to Kettering of General Motors, Professor Millikan, or any first-rate physicist" (par 6). Obviously, simplicity and first-rate physicists do not go together in the same sentence, and Perelman uses this discrepancy to emphasize the difficulty of the kit while simultaneously providing some comic relief. At the beginning of the essay, he describes his difficulty with putting together a closet, and says that "in a period of rapid technological change, however, it was inevitable that a method as cumbersome as the [closet] would be superseded" (2). One would expect that a rapid technological change would make things easier, not harder, yet the toy truck proves especially troublesome to put together.

His hyperbole is another way his humor shines through. At the end of the story, he makes up an ending: him lying in a hospital room. Obviously, no one will hurt themselves that badly when dealing with a simple toy truck, but in emphasizing the unwieldiness of these projects, he went a little overboard. He describes his situation as trapped in a room heated to 340F, which is obviously untrue, but adds to the drama of what he's trying to do. Frankly, his entire debacle with the toy truck is hyperbole, and it amuses the reader and proves his point -- those instructions need to be simplified.

His irony manifests itself in humorous one-liners. He says that the kit "was simplicity itself, easily intelligible to Kettering of General Motors, Professor Millikan, or any first-rate physicist" (par 6). Obviously, simplicity and first-rate physicists do not go together in the same sentence, and Perelman uses this discrepancy to emphasize the difficulty of the kit while simultaneously providing some comic relief. At the beginning of the essay, he describes his difficulty with putting together a closet, and says that "in a period of rapid technological change, however, it was inevitable that a method as cumbersome as the [closet] would be superseded" (2). One would expect that a rapid technological change would make things easier, not harder, yet the toy truck proves especially troublesome to put together.

His hyperbole is another way his humor shines through. At the end of the story, he makes up an ending: him lying in a hospital room. Obviously, no one will hurt themselves that badly when dealing with a simple toy truck, but in emphasizing the unwieldiness of these projects, he went a little overboard. He describes his situation as trapped in a room heated to 340F, which is obviously untrue, but adds to the drama of what he's trying to do. Frankly, his entire debacle with the toy truck is hyperbole, and it amuses the reader and proves his point -- those instructions need to be simplified.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

IRB Intro - The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker

The Language Instinct, by Steven Pinker, takes a unique look at the way language is processed in our brains, which I think is a much more interesting angle than the usual one that is taken, which usually goes along the lines of "look at how weird and jumbled and strange the English language is!" I mean, what do you expect from a language that's hundreds of years in the making? I've always thought it's so fascinating how little kids can pick up language so easily, and how that aptitude is just shut off in our brains the older we get. I'm really excited to learn something new from this book!

Sunday, November 9, 2014

TOW #9 - "CNN Holds Morning Meeting..." (Written)

The full title of this Onion article is "CNN Holds Morning Meeting To Decide What Viewers Should Panic About For Rest of Day", a satirical look at the way mass media stirs up a frenzy over innocuous, or at least non-urgent, news stories. Though the title specifically calls out CNN, this article applies to all major news networks, who are guilty of exaggerating news in order to keep viewers watching. The article includes "quotes" from "senior CNN staffers" to lend to its credibility, although being a satirical article, it only needs this credibility to mimic the format of what it's mocking, i.e. news articles.

This article includes examples of topics that would be aired on a typical news channel in an alarmist manner, such as "the threats posed by pit bulls" and "a potentially dangerous new teen trend...in which kids stay up all night texting". These things are obviously harmless, but the Onion is comparing these ridiculous examples to CNN's everyday lineup of news, making the reader question how serious and urgent many of the stories in the actual news are.

In this article, the people who make these "decisions" are portrayed as flippant about their "responsibilities": "the discourse was briefly derailed by a recounting of the previous night's NFL game and discussions of staff members' upcoming weekend plans". Though we may think of those working for mass media outlets as hard-hitting journalists, when some of the stories that are aired are more closely examined, the reader may realize that they may as well be normal people who don't take their job seriously enough to do research or present an unbiased, non-radical viewpoint.

This article includes examples of topics that would be aired on a typical news channel in an alarmist manner, such as "the threats posed by pit bulls" and "a potentially dangerous new teen trend...in which kids stay up all night texting". These things are obviously harmless, but the Onion is comparing these ridiculous examples to CNN's everyday lineup of news, making the reader question how serious and urgent many of the stories in the actual news are.

In this article, the people who make these "decisions" are portrayed as flippant about their "responsibilities": "the discourse was briefly derailed by a recounting of the previous night's NFL game and discussions of staff members' upcoming weekend plans". Though we may think of those working for mass media outlets as hard-hitting journalists, when some of the stories that are aired are more closely examined, the reader may realize that they may as well be normal people who don't take their job seriously enough to do research or present an unbiased, non-radical viewpoint.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

TOW #8 - "Going Clear" (IRB)

Going Clear, by Lawrence Wright, is a book that was characterized, to me, by its use of pathos and logos. The narrative of the religion Scientology is laid out very clearly, and each step of the way is backed up by primary source documents or accounts. Like any good non-fiction writer, Wright did his research. However, interspersed between the purely factual accounts of events, Wright inserts his personal opinions, which is his right as an author. And although his opinion may agree with the majority (that Scientology is a strange and scammy "religion"), it's his opinion nevertheless. But I think that's the sort of thing one should expect from any sort of book. Nothing is free of bias. I actually enjoyed reading some of his judgments and thinking to myself, "Well, that's not completely true." This book was good at challenging my beliefs and providing me with the evidence to create my own viewpoints while also showing how they could support another.

I think that the author's purpose in writing this book was to delve deeper than most people are willing into the subject of Scientology, and to provide a comprehensive look at its progress, from its beginning to the present. It's a known fact that the Church tends to prosecute those who speak badly about their religion, so Wright took a risk in writing this book. I'm sure he felt it was necessary, though, to exercise his freedom of speech and provide information (biased, sometimes, but sometimes very objective) about an artifact of American culture. His use of quotes, statistics, and documents helped give the reader a good overall view of Scientology's development. It's effectively impossible to have a non-fiction informational book that is not well-researched, and I believe this book was extremely well-researched. However, it also contained perspectives and viewpoints from the author himself and in quotes from people directly involved with the religion that provided some pathos, by making the reader consider their own opinions and feelings regarding the subject.

I think that the author's purpose in writing this book was to delve deeper than most people are willing into the subject of Scientology, and to provide a comprehensive look at its progress, from its beginning to the present. It's a known fact that the Church tends to prosecute those who speak badly about their religion, so Wright took a risk in writing this book. I'm sure he felt it was necessary, though, to exercise his freedom of speech and provide information (biased, sometimes, but sometimes very objective) about an artifact of American culture. His use of quotes, statistics, and documents helped give the reader a good overall view of Scientology's development. It's effectively impossible to have a non-fiction informational book that is not well-researched, and I believe this book was extremely well-researched. However, it also contained perspectives and viewpoints from the author himself and in quotes from people directly involved with the religion that provided some pathos, by making the reader consider their own opinions and feelings regarding the subject.

TOW #7 - "Pets Allowed" (Written)

Pets Allowed, by Patricia Marx, is a comedic tale of her adventures in New York City on five different days with five different "emotional support" animals: a snake, a pig, a turkey, an alpaca, and a turtle. Her purpose is to convince pet owners that the concept of an emotional support animal is ridiculous. Emotional support animals (ESAs) are different from service dogs, who are able to perform specific tasks that aid their owner. ESAs are simply there to comfort their owner, and since that is such a broad definition, Marx proves that you can quickly and easily (for about $100-$200) register any animal, no matter how ridiculous as an ESA.

People obviously take advantage of this. The law does not require any businesses to allow ESAs inside, although it is required that they allow service dogs in. However, there is a gray area in terms of the general public's knowledge of these laws, so Marx was able to take her menagerie into restaurants and stores by showing them a letter from a random therapist she found online that approved her animals for emotional support. She managed to get an alpaca into a historical house (which should never be allowed, for obvious reasons) simply by flashing the letter from her sketchy shrink. Her argument is accentuated by its ridiculousness -- she uses hyperbole by representing the worst-case situation to show how people breaking the law in normal life have potential to cause disturbance and annoyance to others, simply for their own comfort.

Her article was not completely for argumentative purposes, however. If it had, she could have just taken one ridiculous animal out. However, to amass as many humorous anecdotes as possible, she took five animals, each of which created their own unique situations. The article comes with pictures of her pushing the pig around in a stroller, or carrying him into the cabin on the plane (she brought her pig on a plane!) to show the pilot, and pictures of her turkey on a bus and her snake wrapped around her neck. She aims to amuse and use that amusement she creates in the reader to further her argument.

People obviously take advantage of this. The law does not require any businesses to allow ESAs inside, although it is required that they allow service dogs in. However, there is a gray area in terms of the general public's knowledge of these laws, so Marx was able to take her menagerie into restaurants and stores by showing them a letter from a random therapist she found online that approved her animals for emotional support. She managed to get an alpaca into a historical house (which should never be allowed, for obvious reasons) simply by flashing the letter from her sketchy shrink. Her argument is accentuated by its ridiculousness -- she uses hyperbole by representing the worst-case situation to show how people breaking the law in normal life have potential to cause disturbance and annoyance to others, simply for their own comfort.

Her article was not completely for argumentative purposes, however. If it had, she could have just taken one ridiculous animal out. However, to amass as many humorous anecdotes as possible, she took five animals, each of which created their own unique situations. The article comes with pictures of her pushing the pig around in a stroller, or carrying him into the cabin on the plane (she brought her pig on a plane!) to show the pilot, and pictures of her turkey on a bus and her snake wrapped around her neck. She aims to amuse and use that amusement she creates in the reader to further her argument.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

TOW #6 - "Don't Eat Before Reading This" (Written)

This piece by Anthony Bourdain, who worked his way up to owning his own restaurant from being a dishwasher, reveals the secrets behind a usual New York professional kitchen that most people don't know about. His diction is very frank - he does not hold back from telling the reader about the disgusting and disease-ridden conditions going on behind their favorite restaurants. He uses words like "cruelty and decay" to really get across his message that kitchens are not fairy tale lands.

He uses juxtaposition of the quaint French terms that people think chefs use with the coarse Spanish that they actually use. This helps emphasize the difference between perception and reality. However, he assures the reader that while there can be violent spats, no one actually uses their readily available weapons (knives and meat mallets) for evil. So there is a soft side to the kitchen life, but it doesn't come out very often.

He references the Department of Health a few times, mostly to tell the reader that many of their regulations are ignored. This may be the reason for his humorous title, which tells the reader that what they're about to read will not sit well with them or their dinner. It also establishes a light-hearted tone in what might otherwise be a serious exposé. He doesn't believe that anything that goes on in these kitchens is truly bad, just unfortunate truths of the industry.

Bourdan introduces terms to the reader and defines them right away, which helps give them a quick insider's look. Just learning the terminology of a certain profession gives a really good glimpse into how it works and what the most important aspects of it are -- since the things that are used most often will probably get unusual names. And if a name is disparaging (like "coffee filters" for the tall paper chef hats most people imagine), it clues you in that that object is less important, or annoying, or silly.

He uses juxtaposition of the quaint French terms that people think chefs use with the coarse Spanish that they actually use. This helps emphasize the difference between perception and reality. However, he assures the reader that while there can be violent spats, no one actually uses their readily available weapons (knives and meat mallets) for evil. So there is a soft side to the kitchen life, but it doesn't come out very often.

He references the Department of Health a few times, mostly to tell the reader that many of their regulations are ignored. This may be the reason for his humorous title, which tells the reader that what they're about to read will not sit well with them or their dinner. It also establishes a light-hearted tone in what might otherwise be a serious exposé. He doesn't believe that anything that goes on in these kitchens is truly bad, just unfortunate truths of the industry.

Bourdan introduces terms to the reader and defines them right away, which helps give them a quick insider's look. Just learning the terminology of a certain profession gives a really good glimpse into how it works and what the most important aspects of it are -- since the things that are used most often will probably get unusual names. And if a name is disparaging (like "coffee filters" for the tall paper chef hats most people imagine), it clues you in that that object is less important, or annoying, or silly.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

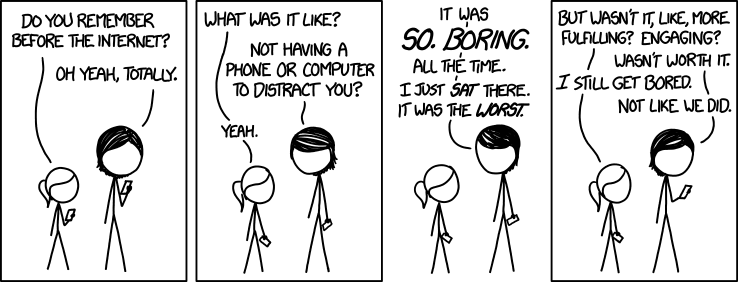

TOW #5 - "Before the Internet" (Visual)

This is a webcomic written/drawn by Randall Munroe, who has been making comics like these since 2005, and it features a little girl holding a phone, talking to an adult also holding a phone. It pokes fun at how everyone laments the loss of a "fulfilling" and "real" life after the advent of the internet. The young girl, having heard this her whole life, assumes it must have been better back then, but is quickly shot down by the adult, who assures her that it was terrible.

Readers of this comic, the majority of whom are in their twenties to thirties (though there are younger readers), lived most of their childhood without a constant stream of internet in their hands. They themselves are probably guilty of trumpeting how they miss the "good old days" - but halfway through the comic, when the expected response from the adult is "oh, life was better, we went outside, we were more creative, etc." -- she gives a frank, honest reply. One can almost hear the tone of voice she uses, which the author conveys with the large, bold, italic text in the middle of the comic.

The stick figure characters are drawn in black and white, with no facial expressions. All the emotions have to be conveyed with stance and word choice, which this author does very effectively. The adult looks at the child very seriously when telling her how boring it was, then turns nonchalantly back to her phone when brushing off the kid's clarifications. "Wasn't worth it." It's obviously said in an off-hand, "of-course-not" manner, which the reader infers simply from the position of the stick figure's head and the short sentence.

Something that this author is famous for is putting mouseover text on all his comics, meaning that if you hover over the picture for a few seconds, a box will pop up with a continuation of the joke. The text on this one is "We watched DAYTIME TV. Do you realize how soul-crushing it was? I'd rather eat an iPad than go back to watching daytime TV." It's a silly joke for readers who are "in on the secret" to discover. It also adds a little more to the "argument" of the comic.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

TOW #4 - "Going Clear" (IRB)

So far, I'm really enjoying this book about Scientology by Lawrence Wright. The part that I'm most interested in is still to come, which is why so many celebrities are involved in the Church. L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, was a science fiction writer who tried to break into the screenwriting industry and lived in Hollywood for some time, so I can see how it got tied into that culture, but I'm interested in the specifics of that process.

The main rhetorical device I've noticed this author using is juxtaposition, and I think it's in an attempt to discredit Hubbard and his ideas. Lawrence relates a quote from one of Hubbard's memoirs or books, and the follows it up with an official record that says the exact opposite. For instance, Hubbard describes reading his psychiatric examination record: "I got to the end and it said, 'In short, this officer has no neurotic or psychotic tendencies of any kind whatsoever'" (Wright 41). The sentence directly afterwards is in parentheses and is in Wright's words, saying "There is no psychiatric evaluation contained in Hubbard's medical records" (Wright 41). There are multiple similar instances, each one further serving to prove that Hubbard is an unreliable, pathological liar. This helps to paint of picture of the religion, which is widely considered a scam by the general public. It also possibly prevents the reader from thinking, "Hmm, yeah, I agree with this Hubbard guy's ideas!" while reading this book, which is intended to be a reveal-all of Scientology and does not at all endorse his ideas.

The rhetorical mode of this book (at least for the first section) is narrative. I'm not sure how the second half of the book will be, but the beginning details Hubbard's life and his journey towards creating Scientology. It draws from primary source documents like his memoirs, journals, books, and accounts from people who were close to him. This rhetorical mode helps put all the events leading up to the creation of the religion in chronological order and show their logical progression.

I'm extremely interested in how the rest of this book will expand upon the foundation it built (description of Hubbard, description of the religion) in the first half. It seems very promising!

The main rhetorical device I've noticed this author using is juxtaposition, and I think it's in an attempt to discredit Hubbard and his ideas. Lawrence relates a quote from one of Hubbard's memoirs or books, and the follows it up with an official record that says the exact opposite. For instance, Hubbard describes reading his psychiatric examination record: "I got to the end and it said, 'In short, this officer has no neurotic or psychotic tendencies of any kind whatsoever'" (Wright 41). The sentence directly afterwards is in parentheses and is in Wright's words, saying "There is no psychiatric evaluation contained in Hubbard's medical records" (Wright 41). There are multiple similar instances, each one further serving to prove that Hubbard is an unreliable, pathological liar. This helps to paint of picture of the religion, which is widely considered a scam by the general public. It also possibly prevents the reader from thinking, "Hmm, yeah, I agree with this Hubbard guy's ideas!" while reading this book, which is intended to be a reveal-all of Scientology and does not at all endorse his ideas.

The rhetorical mode of this book (at least for the first section) is narrative. I'm not sure how the second half of the book will be, but the beginning details Hubbard's life and his journey towards creating Scientology. It draws from primary source documents like his memoirs, journals, books, and accounts from people who were close to him. This rhetorical mode helps put all the events leading up to the creation of the religion in chronological order and show their logical progression.

I'm extremely interested in how the rest of this book will expand upon the foundation it built (description of Hubbard, description of the religion) in the first half. It seems very promising!

Sunday, September 21, 2014

TOW #3 - Visual

This illustration is drawn by Paul Noth, who regularly makes cartoons for the New Yorker, as well as the Wall Street Journal; he was also a writer for "Late Night with Conan O'Brien", so he's an experienced comedy writer. The regular readers of the New Yorkers can be assumed to be knowledgeable about history and have cynical senses of humor. This cartoon plays on the detachment that royalty historical had from their subjects -- like Marie Antoinette's "Then let them eat cake!", which never happened, but wasn't far from her reality. Some of them have had very strange senses of humor as well, like Charles II finding a subject's plan to steal his crown jewels hilarious.

In order to be recognizable at a glance to the reader, the king is wearing the traditional robes and crown that come to mind when thinking of a king. The jester is wearing the jester hat and silly clothing associated with that profession, and the poor family is wearing torn and ragged clothes that are more textured and less clean-looking than the king and jester's. The author of this text carefully drew the clothing of each subject to be immediately recognizable to the reader -- since the longer it takes them to understand the punch line, the less funny it gets.

I believe the author accomplished his purpose because I thought it was funny -- but I'm not the only one he's trying to please. However, I think this would appeal to wide audiences, because most people learned enough about history in their years at school to understand the context of this cartoon. Often, people will think that something is funny just because they understand the joke, which is the effect of feeling like you're in a "group" that understands. Obviously, the king here does not understand the humor of the situation and is not in that special group. But he's a king, so he's probably fine.

Sunday, September 14, 2014

TOW #2 - "Stepping Out" (Written)

Stepping Out, by David Sedaris (published in the New Yorker), is an article that's more of a memoir. It details his journey of getting something called a FitBit, which is a bracelet that counts the steps of the wearer. He became obsessed with it, and eventually worked his way up to walking sixty thousands steps (or 25 and a half miles (almost the length of a marathon!)) each day. While he walked, he picked up trash and saw interesting things -- he watched a calf being born on one trip.

He seems to simultaneously warn the reader against the obsession he developed towards his walking, while extolling its virtues. He got a garbage truck named after him for all the trash he collected off the streets while walking. And the article concludes with his FitBit breaking. He lasts five hours before rushing to order another one. I think whatever message he was delivering about his obsession was secondary, however. I think he views his obsession as a (slightly unhealthy) vehicle for the new experiences he had with the FitBit. He talks about the perspectives that it opens his eyes to: he begins with an anecdote about how he covered 10,000 steps easily over the course of the day by walking down the stairs to his door when a visitor came. He has discussions with them about gypsies (also called Pikeys, Tinkers, or "travellers"), notices the combinations of different kinds of trash on the ground that tell their own story, and is fascinated by dead beavers being fed on by slugs. These things all tell stories of their own, which wouldn't be noticed or cared about if not for his obsession with walking.

He uses dialogue in his story to incorporate other points of view from people he talks to, such as his partner Hugh asking him why he feels the need to walk so far each day. He also uses vivid imagery and humor concerning the animals he sees - "Once, [there] was a toffee-colored cow with two feet sticking out of her...Then she got up and began grazing, still with those feet sticking out." It helps engage the reader in the journey he's taking, and help them see his overall purpose, to persuade readers that the perspectives of others are essential in our individual lives. I think he achieved that purpose.

He seems to simultaneously warn the reader against the obsession he developed towards his walking, while extolling its virtues. He got a garbage truck named after him for all the trash he collected off the streets while walking. And the article concludes with his FitBit breaking. He lasts five hours before rushing to order another one. I think whatever message he was delivering about his obsession was secondary, however. I think he views his obsession as a (slightly unhealthy) vehicle for the new experiences he had with the FitBit. He talks about the perspectives that it opens his eyes to: he begins with an anecdote about how he covered 10,000 steps easily over the course of the day by walking down the stairs to his door when a visitor came. He has discussions with them about gypsies (also called Pikeys, Tinkers, or "travellers"), notices the combinations of different kinds of trash on the ground that tell their own story, and is fascinated by dead beavers being fed on by slugs. These things all tell stories of their own, which wouldn't be noticed or cared about if not for his obsession with walking.

He uses dialogue in his story to incorporate other points of view from people he talks to, such as his partner Hugh asking him why he feels the need to walk so far each day. He also uses vivid imagery and humor concerning the animals he sees - "Once, [there] was a toffee-colored cow with two feet sticking out of her...Then she got up and began grazing, still with those feet sticking out." It helps engage the reader in the journey he's taking, and help them see his overall purpose, to persuade readers that the perspectives of others are essential in our individual lives. I think he achieved that purpose.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

IRB Intro #1 - Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, & the Prison of Belief

Going Clear by Lawrence Wright is a book that explores the origins of Scientology, its current practices, and the way current and former members feel about the religion. I chose it because I've always been interested in religions that are outside the mainstream (such as the Church of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) and Jehovah's Witnesses). It's fascinating to learn how these religious are developed, how they recruit members, and how much of their reputations as a "scam" or a "cult" are deserved. The first chapter of the book teased a reveal of some of Scientology's deepest secrets that only the highest-level members get to know, so I am absolutely ready to keep reading and find out what they are!

Sunday, September 7, 2014

TOW #1 - How to Say Nothing in 500 Words

This essay was written by Paul Roberts, who wrote several textbooks about the English language and its use, making him a person that can be trusted when it comes to writing pages of prose about largely uninteresting subjects. He explains techniques that the reader can use in their own essays to make them more captivating and interesting. His target audience is college students, who are still stuck in their old high school writing habits and clichés.

He uses an example of a typical essay - an opinion piece on college sports - and shows how a normal student would go about composing it. He uses the second person, which makes the reader feel as though the advice is addressed directly to them, and it helps them see more clearly the ways that they can apply it to their own writing. It also makes the author seem like a more familiar figure to the reader, so they're more likely to trust his advice and follow it. Roberts also focuses his essay around a central example to make his suggestions more concrete and to exemplify the way they can be used in an essay. Additionally, he uses humor and informal language to soften the criticisms that he throws at the reader.

This writer is obviously tired of students writing and rewriting the same kind of paper over and over again, with no originality whatsoever. His purpose was to rectify that, and to demonstrate several common mistakes that can be easily corrected to vastly improve the quality of writing. I believe he accomplished this purpose, because by the end of the essay, I was newly aware of the issues in my own writing, and informed of ways I could correct them. The essay was well organized with headings that pointed precisely to specific ways that creativity could be added to an otherwise boring paper. I would say that anyone who reads this is very likely to employ this essay's techniques in their own writing.

He uses an example of a typical essay - an opinion piece on college sports - and shows how a normal student would go about composing it. He uses the second person, which makes the reader feel as though the advice is addressed directly to them, and it helps them see more clearly the ways that they can apply it to their own writing. It also makes the author seem like a more familiar figure to the reader, so they're more likely to trust his advice and follow it. Roberts also focuses his essay around a central example to make his suggestions more concrete and to exemplify the way they can be used in an essay. Additionally, he uses humor and informal language to soften the criticisms that he throws at the reader.

This writer is obviously tired of students writing and rewriting the same kind of paper over and over again, with no originality whatsoever. His purpose was to rectify that, and to demonstrate several common mistakes that can be easily corrected to vastly improve the quality of writing. I believe he accomplished this purpose, because by the end of the essay, I was newly aware of the issues in my own writing, and informed of ways I could correct them. The essay was well organized with headings that pointed precisely to specific ways that creativity could be added to an otherwise boring paper. I would say that anyone who reads this is very likely to employ this essay's techniques in their own writing.

Friday, August 29, 2014

Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying by Adrienne Rich

The essay Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying, by Adrienne Rich, investigates the relationship women have with lying and the author encourages women to let go of their dependence on lying for a more fulfilling life. Rich is a well-known poet and feminist of the 20th century; she has won numerous prizes for her writing. She wrote this piece in 1977, which was soon after she had publicly come out as a lesbian and began a relationship with the novelist Michelle Cliff, which lasted until her death. She has therefore had the writing and personal experiences to allow her to write such an emotional and effective argument against lying. In this essay, Rich points out the destructiveness of a need for manipulation and deceit in relationships, and urges the reader to leave behind the compulsion to lie in order to protect themselves and their emotions. She directs her words at women who lie to others because they have been taught to do so, or because they are not expected to tell the truth. Her use of devices like parallelism (she repeats "It is important to do this" thrice when endorsing truth-telling (414)) and stating contradictory aphorisms to emphasize the struggle involved in breaking the habit of lying, helps solidify in the reader's mind that Rich is passionate and believes in her argument.

I found this essay to be very compelling. The author paints a picture of sisterhood between women while simultaneously laying out the dangers of lying: "The liar lives in fear of losing control...to be vulnerable to another person means for her the loss of control" (413). And following the guilt she induces in liars, she sings the praises of being truthful: "It is important to do this because in so doing we do justice to our own complexity" (414). Very strong emotions are present in this essay, and they work in tandem to encourage the reader to be truthful to herself and to others.

I found this essay to be very compelling. The author paints a picture of sisterhood between women while simultaneously laying out the dangers of lying: "The liar lives in fear of losing control...to be vulnerable to another person means for her the loss of control" (413). And following the guilt she induces in liars, she sings the praises of being truthful: "It is important to do this because in so doing we do justice to our own complexity" (414). Very strong emotions are present in this essay, and they work in tandem to encourage the reader to be truthful to herself and to others.

|

| Rich's argument in defense of the truth source: http://www.rugusavay.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Adrienne-Rich-Quotes-2.jpg |

Putting Daddy On by Tom Wolfe

This essay, Putting Daddy On, by Tom Wolfe, describes a father whose son, Ben, has dropped out of a prestigious university to live in the slums and, in the father's eyes, waste his life and his potential. The author was described by Kurt Vonnegut as "a genius who will do anything to get attention." Wolfe also influenced a movement in journalism in which literary devices are used to present objective stories, and this essay falls under that technique. The characters in this essay demonstrate a father's desire to stay relevant and fit in with his own social crowd, while still wanting to be relevant to his own son; however, his son is beginning to find his own life and doesn't want to be tied down by his father. The time period reflects these changes and revolutions in their relationships. It was written in 1964, the beginning of the "cultural decade" of The Sixties, which was the start of civil rights and gay rights movements, as well as a revolution in music.

The author introduces a character who uses rhetorical devices in his own speech, who uses a lot of "ironic metonymy and metaphor" (280). The essay ends on a metaphor, when Parker says, "I couldn't say anything to him...I couldn't make anything skip across the pond" (287). It instills the sense of a large distance between father and son, one which cannot be crossed easily or reliably. The audience of this essay is the people who are of the same demographic as the main character, Parker. They are getting older and having difficulty coping with the rapid changes in society and those around them. Parker understands everything, but doesn't want to accept the motives behind why his son is breaking off from him.

I think that Tom Wolfe did a good job of creating relatable characters to express the desire to connect during a time when your own and your loved ones' interests are changing. The father's exasperation and the son's embarrassment are elements that exist in nearly all familial relationships. Anyone can learn from and appreciate the message of this essay.

The author introduces a character who uses rhetorical devices in his own speech, who uses a lot of "ironic metonymy and metaphor" (280). The essay ends on a metaphor, when Parker says, "I couldn't say anything to him...I couldn't make anything skip across the pond" (287). It instills the sense of a large distance between father and son, one which cannot be crossed easily or reliably. The audience of this essay is the people who are of the same demographic as the main character, Parker. They are getting older and having difficulty coping with the rapid changes in society and those around them. Parker understands everything, but doesn't want to accept the motives behind why his son is breaking off from him.

I think that Tom Wolfe did a good job of creating relatable characters to express the desire to connect during a time when your own and your loved ones' interests are changing. The father's exasperation and the son's embarrassment are elements that exist in nearly all familial relationships. Anyone can learn from and appreciate the message of this essay.

|

| Skipping stones across a pond requires more precision and intuitive understanding than Ben and his father have in their relationship. source: http://www.alanbray.com/images/SkippingStones.jpg |

Corn-Pone Opinions by Mark Twain

The essay Corn-Pone Opinions, by Mark Twain, describes to the reader his theory about where and why people get their opinions. He believes that people hold opinions that allow them to approve of themselves, and that often, the way people judge their own worth is whether others approve of them. This essay was written in 1901, but it starts with an anecdote from Twain's memory that he dates to about 1850. The terminology in the title is outdated; corn-pone is what we would call cornbread now. Although he uses examples (like hoopskirts) that are irrelevant to us now, they were very pertinent examples to his target audience: early 20th century America, to whom Twain was trying to reveal the way that they choose their opinions. Once they understand, they can be more aware of others' viewpoints and more open to changing their opinion when shown evidence. To emphasize this understanding, Twain provides a list of religions and political viewpoints using parallel construction: "Mohammedans are Mohammedans because they are born and reared among that sect...we know why Catholics are Catholics; why Presbyterians are Presbyterians..." (4).

Mark Twain is a celebrated author (he wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn), and he is well-known for his humor. Although this essay isn't humorous, I think his past writings substantiate his claims, since humorists work to see true human nature (and then turn around and make fun of it). I don't think his purpose was to change anything, or make people choose opinions based on cold, hard facts instead of self-approval. He says, "We all do no end of feeling, and we mistake it for thinking. And out of it we get an aggregation which we consider a boon. Its name is Public Opinion...Some think it is the Voice of God" (5). He includes himself in the "we", showing that he does it; everyone does it. But he warns against taking it as gospel, or insisting that an opinion is correct when it's merely popular. I don't think that his purpose was achieved, but through no fault of his own. There still exist people who would like to believe that their opinions are theirs alone and/or absolutely correct. It is difficult to escape these thoughts, and just a few people reading an essay will not change all of society.

Mark Twain is a celebrated author (he wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn), and he is well-known for his humor. Although this essay isn't humorous, I think his past writings substantiate his claims, since humorists work to see true human nature (and then turn around and make fun of it). I don't think his purpose was to change anything, or make people choose opinions based on cold, hard facts instead of self-approval. He says, "We all do no end of feeling, and we mistake it for thinking. And out of it we get an aggregation which we consider a boon. Its name is Public Opinion...Some think it is the Voice of God" (5). He includes himself in the "we", showing that he does it; everyone does it. But he warns against taking it as gospel, or insisting that an opinion is correct when it's merely popular. I don't think that his purpose was achieved, but through no fault of his own. There still exist people who would like to believe that their opinions are theirs alone and/or absolutely correct. It is difficult to escape these thoughts, and just a few people reading an essay will not change all of society.

|

| Mark Twain's Opinion on Opinions source: http://universalfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Mark-Twain-1.jpg |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)